There are two significant aspects to OCD, obsessions and compulsions. The process of how with OCD our thoughts (obsessions) and our behaviours (compulsions) are entwined is far more complex, so we look at that later in this section, on this page we will help you understand what obsessions are.

People with OCD experience unwanted obsessions which take the form of persistent and uncontrollable thoughts, although obsessions can sometimes be persistent images, impulses, worries, fears or doubts or a combination of all these. They’re always intrusive, unwanted, disturbing and most importantly significantly interfere with the sufferers ability to function on a day-to-day basis as they are incredibly difficult to ignore.

The word ‘obsession’ comes from the Latin ‘obsidere’ which means ‘to besiege’.The problem is that the person with OCD will become besieged by the obsessive thoughts. In fact the word ‘obsession’ comes from the Latin ‘obsidere’ which means ‘to besiege’. Naturally the sufferer neither wants nor welcomes the obsessional thoughts which cause such deep anguish and despair, the person being besieged will go to extreme lengths to block and resist them. Invariably they return within a short period of time, often lasting hours if not days, which can leave the person both mentally and physically exhausted and drained.

People with OCD usually realise that their obsessional thoughts are irrational, but at the same time feels so very real and they believe the only way to relieve the anxiety caused by them is to perform compulsive behaviours (which includes avoidance and seeking reassurance). These compulsive behaviours are carried out to prevent perceived harm happening to themselves or, more often than not to a loved one, even when there is no correlation between their thoughts and compulsive behaviour.

For those without OCD it can be hard to understand what drives a person to seemingly nonsensical behaviours (or worries) for hours at a time. So if we were to suggest something horrific happening to a loved one, something so terrible you dare not contemplate such awfulness for even the briefest of moments, then understanding the fact that for a person affected by Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder such horrible intrusive thoughts plague them constantly throughout the day, the person without OCD may have the briefest of insights into what’s going on with someone with OCD and why such nonsensical behaviours are carried out to prevent the perceived danger from becoming a reality.

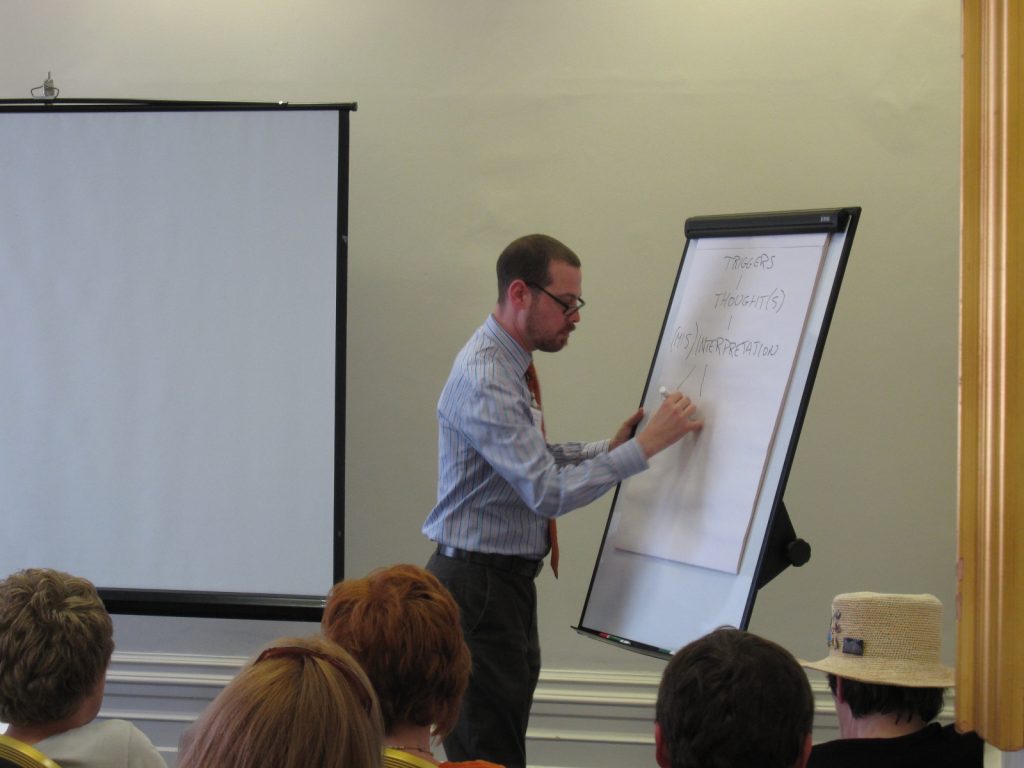

To try and illustrate this point a little more graphically, when teaching mental health professionals about OCD, teaching professors will often conduct a little experiment with their audience, starting out by asking the audience to agree with a statement that saying something or thinking something doesn’t mean it will come true, that our thoughts are not magical and can’t make things happen. For example, thinking about winning the lottery and how your life will change doesn’t mean you will win the lottery. The teaching expert will then go on to ask the audience, which we have seen include trained clinical psychologist and psychiatrists, to write down the name of a loved one on a bit of paper and then further add a statement about something horrific happening to that person. Despite all those highly qualified doctors moments previously agreeing that thinking or saying something doesn’t mean it will magically come true, they’re nearly always all unable to write down the specific statement about something horrific happening to their loved one, or those that do then destroy that bit of paper into lots and lots of tiny little shreds.

This exercise perfectly illustrates two things to help people understand Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, firstly the power of a single unwanted intrusive thought (obsession) to cause such distress and secondly how such thoughts can lead to seemingly nonsensical compulsions (i.e. ripping the piece of paper into many shreds).

With OCD what’s important to note is that these obsessional thoughts are repetitive and are not voluntarily produced.With OCD what’s important to note is that these obsessional thoughts are repetitive and are not voluntarily produced, which in itself causes more distress to the sufferer. All obsessional thoughts (regardless of content) usually produce a sense of discomfort, or a ‘feeling’ of unease. Some people describe it to be an increase or trigger of anxiety, but for others it is simply that ‘feeling’ of general unease, tension and/or discomfort.

Sometimes, especially in the case of harm or sexual related intrusive thoughts the person will struggle to identify the difference between their obsessive thoughts and reality, mistakenly believing that because they have had the thought it somehow means the thoughts are a desire they want to act on.

It’s important to understand that in the case of some of the more extreme obsessive thoughts of a violent or sexual nature, such as worries about being a paedophile, that the thoughts do not precede intent. More on this in a later chapter when we discuss risk assessment in OCD for health professionals.

The brain is a powerful organ, and in many types of OCD, especially those focused on themes around sexuality it can cause parts of our body to react when we focus on our thoughts, even if we desperately don’t want it to. For example if we tell you to focus on your left foot, think about your left foot and chances are you will feel a little tingly feel in your left foot. So for those people with OCD whose obsessional fear is about inappropriate sexual acts may find their body causes physical reactions to their genitals. This is perfectly normal, and should not alarm the person suffering or a health professional treating someone with this form of OCD, it doesn’t indicate sexual orientation and preferences, it simply means our thoughts are leading to involuntary and unwanted bodily sensations.

To sufferers and non-sufferers alike, the thoughts and fears related to OCD can often seem profoundly shocking, however it must be stressed again that they are just thoughts, and they are not voluntarily produced. Neither are they fantasies or impulses which will be acted upon. What we do know is that people living with OCD are the least likely people to actually act on such thoughts.

In these cases it is perhaps worth mentioning that evidence shows us that obsessional thoughts are quite common in the general population, not just for those that suffer with OCD. Researchers in the US, UK and Canada have shown that up-to 80% of people report unwanted intrusive thoughts with content that is often identical to that of obsessions found in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder.

In their research, Byers, Purdon and Clark (1998) took a sample of 171 university students on a psychology course in Canada with a mean age of 19.5, and in previous research Purdon and Clark (1993) a sample of 293 students and demonstrated that even people without any mental health problems reported having intrusive thoughts of an aggressive, religious, or sexual nature, including thoughts of inappropriate sexual interaction with someone they shouldn’t.

The table below shows the results of research from the Purdon and Clark study of 293 university students (198 female, 95 male), none of which had a diagnosed mental health condition. The columns shows the percentage of men and women who said they had experienced that particular thought.

What this research shows us is that many, many people without any obsessional problem have exactly the same types of unwanted thoughts as people with OCD. The main difference is that people with OCD report obsessions which are more intense, frequent and difficult to control.

The important thing to remember is that the occasional intrusive thought, even a disturbing and horrific one, is normal for every individual, even those without OCD. It also shows us that it is not the actual thoughts themselves that are the problem, but the way those with OCD respond to those thoughts.

This is important to remember it’s not the thought itself that is the problem, it is the way people interpret and deal with the thought, which we will explore more on the understanding how OCD works page elsewhere in this chapter.

In 2005 The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) published their guidelines for the treatment of OCD and BDD, within their findings they published this table to illustrate the types of obsessive fears that people with OCD have reported.

| Obsession | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Contamination from dirt, germs, viruses (e.g. HIV), bodily fluids or faeces, chemicals, sticky substances, dangerous materials (e.g. asbestos) | 37.80% |

| Fear of harm (e.g. door locks are not safe) | 23.60% |

| Excessive concern with order or symmetry | 10.00% |

| Obsessions with the body or physical symptoms | 7.20% |

| Religious, sacrilegious or blasphemous thoughts | 5.90% |

| Sexual thoughts (e.g. being a paedophile or a homosexual) | 5.50% |

| Urge to hoard useless or worn out possessions | 4.80% |

| Thoughts of violence or aggression (e.g. stabbing one’s baby) | 4.30% |

The table above is perhaps a good example of the types of obsessive fears that people with OCD will experience. However, in different parts of the world where different beliefs are more prevalent these percentages may changes. For example, countries where religion is a prominent part of everyday life, obsessions around religious thoughts may become more common.

Other examples of common obsessions include:

- Worrying that you or something/someone/somewhere is contaminated.

- Worrying about catching HIV/AIDS or other media publicised illnesses such as Bird Flu or Swine Flu.

- Worrying that everything must look and feel arranged at a specific position (sometimes symmetrically) so everything feels ‘just right’.

- Worrying about causing physical or sexual harm to yourself or others.

- Unwanted and unpleasant sexual thoughts and feelings about sexuality or the fear of acting inappropriately towards children.

- Worrying that something terrible will happen.

- Unwanted and intrusive thoughts about violence.

- Fear of something bad happening unless checked (i.e. property will be broken into/burn down).

- Worrying that you have caused an accident whilst driving.

- Having the unpleasant feeling that you are about to shout out obscenities in public.

All of these are the ‘worry/fear’ which is the obsession, rather than the behaviour which would be the compulsion.

This list of obsessions is by no means an exhaustive list and there are many more obsessions not listed here, you can read more about different types of OCD elsewhere in the chapter. However if you’re experiencing distressing and unwanted obsessions not listed here this does not mean it is definitely not OCD, so if these impact significantly on your everyday functioning this could still represent a principal component in the clinical diagnosis of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and you should consult a doctor for a formal diagnosis.

What to read next: