Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, commonly referred to as CBT, remains the treatment of choice for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) here in the UK and is available through the NHS. It’s important that those struggling with OCD try and understand the principles behind CBT.

CBT is used successfully as a treatment for many psychological problems, including OCD and other anxiety problems such as panic, post-traumatic stress disorder and social phobia. It also figures in the treatment of eating disorders, addictions and psychosis.

CBT is a form of talking therapy, however unlike other talking therapies like counselling, it is much more structured and tailored around the individuals ‘here and now’ problems, and rarely focuses on the patient’s past. CBT is also meant to be a short term therapy lasting weeks and months rather than years. Whilst we are always open to other therapies, for the majority, the evidence shows CBT is the treatment of choice for OCD.

Research has shown that 75% of people with OCD are significantly helped by Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, with some local IAPT services reporting recovery rates of up to 80%. What’s more, this form of therapy does not have any risks or side effects associated with it, which is why it remains the treatment of choice for tackling OCD by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), and specialist centres such as the Centre for Anxiety Disorders and Trauma (CADAT).

There are also no limits to how many times you can try CBT. What we mean by that is if you have tried CBT once or twice (or more) with limited success, there is no reason you can’t work with another therapist, perhaps an OCD specialist and have a completely different experience. In the last section we used a driving analogy to describe anxiety, well if we return to a driving analogy, CBT is a bit like learning to drive, some people need one course of lessons (therapy) to pass their test, but others need two or three courses, perhaps with a different instructor (therapist), but if they keep working at it, there is no reason to believe they can’t eventually pass their test.

In many cases, CBT alone is highly effective in treating OCD, but for some a combination of CBT and medication is a more effective treatment package, especially if there is co-morbidity like depression. Medication can be helpful in reducing anxiety enough for a person to start, and eventually succeed, in therapy.

But what is CBT?

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy helps the patient explore and understand alternative ways of thinking and challenging their beliefs through behavioural exercises, Dr Victoria Bream explains…

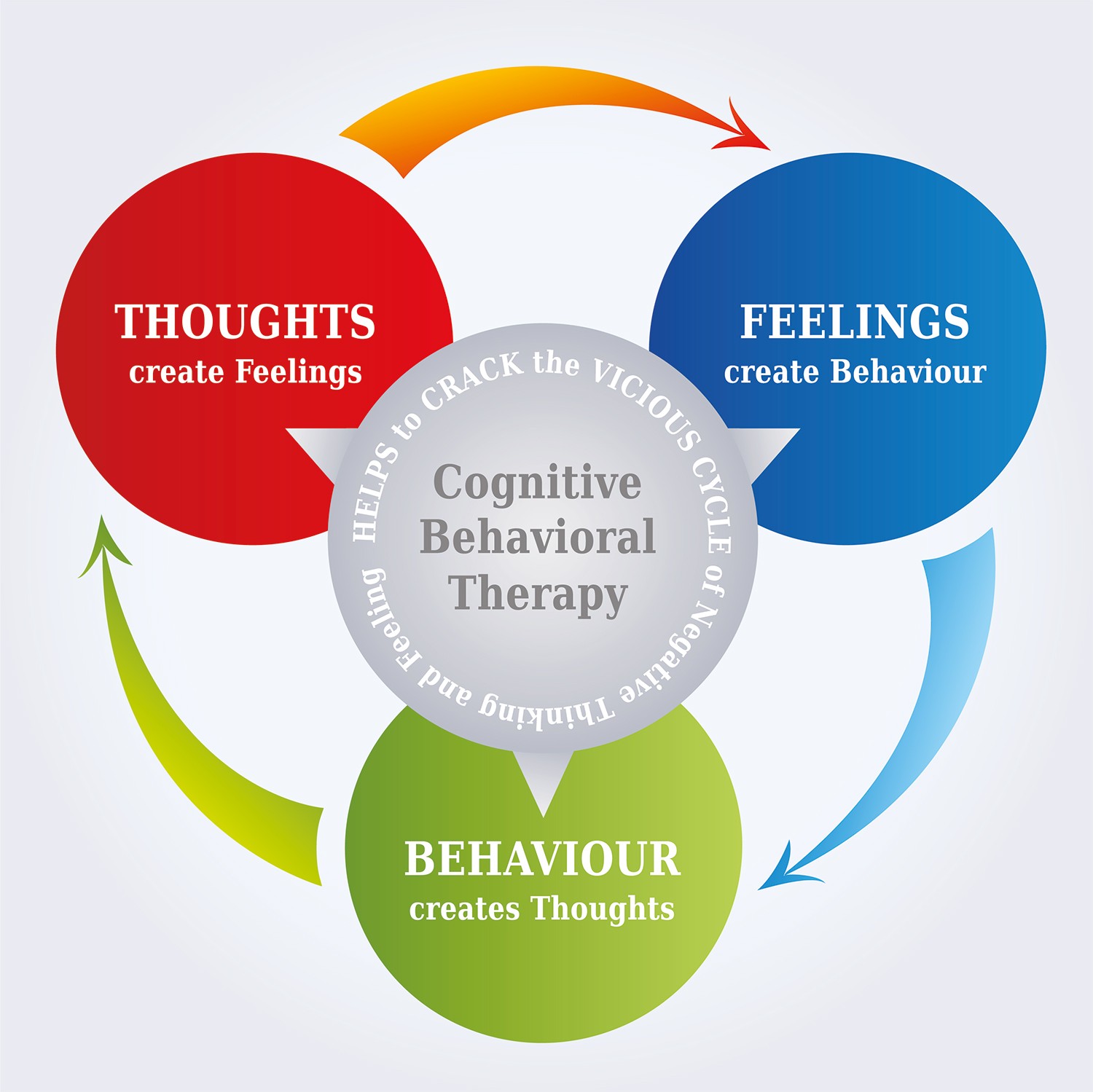

CBT makes use of two evidence-based behaviour techniques, Cognitive Therapy (C) that looks at how we think, and Behaviour Therapy (B) which looks at how this affects what we do. In treatment we consider other ways of thinking (C), and how this would affect the way we behave (B).

It’s based on the concept that your thoughts, feelings and actions are interconnected, and that negative thoughts and feelings can trap you in a vicious cycle, as the image perfectly illustrates.

It’s based on the concept that your thoughts, feelings and actions are interconnected, and that negative thoughts and feelings can trap you in a vicious cycle, as the image perfectly illustrates.

The principal aim of this therapeutic approach is to enable the person to become their own therapist and to provide them with the knowledge and tools to continue working towards complete recovery from OCD.

What we know from research is that almost everyone has intrusive thoughts that are either non-sensical or alarming. The aim of CBT isn’t to never have these thoughts, because intrusive thoughts cannot be avoided, but instead to help a person with OCD to identify and challenge the patterns of thought that cause their anxiety, distress and compulsive behaviours.

What therapy teaches the person with OCD is that it’s not the thoughts themselves that are the problem; it’s what the person makes of those thoughts, and how they respond to them. CBT helps us understand the fears we associate with our thoughts, which as mentioned in the types of OCD page, can often be difficult to recognise.

A good way of understanding how different responses to thoughts can affect the way we behave can be demonstrated in the example below.

- It’s the middle of the night, you’re in bed. You hear a noise from downstairs.

- You might think: ‘It’s the stupid cat again’, feel angry, put your head under the pillow and try to go back to sleep.

- You might think: ‘It’s my partner coming in, I haven’t seen them all day!’, feel happy and get out of bed to say ‘hello’.

- You might think: ‘It’s a burglar’, feel frightened and call the police.

What this example shows is that the same event can make people feel completely different emotions (angry, happy, anxious) and result in them behaving in very different ways, due to their different beliefs about the event. CBT is based on this intuitive understanding of how we think effecting how we behave.

So how does this help us understand how to treat OCD? We believe that OCD works in exactly the same way:

- A disturbing image crosses your mind: you throwing your dog under a train.

- You might think: ‘Damn it, that’s made me forget what I was going to say’ and feel angry, and frown.

- You might think: ‘Wow, what a creative and funny person I am! I’m going to write that down in joke form’ and feel happy that your mind can be so creative.

- You might think: ‘Because I’ve thought that, I must want it to happen, therefore I must be sure I try to undo it’. You then feel anxious, check, seek reassurance and ultimately avoid taking the dog near the train track.

In summary, it’s not the thoughts themselves that are the focus of treatment; it’s what we make of those thoughts in the first place and how we react to them.

In treatment for OCD, one of the first things a person will be asked to do is to think of a recent specific example of when their OCD was really severe. They will be asked to go into a lot of detail, and try and understand what thought(s) (or doubts, images or urges) popped into their head at this time. For example some intrusive thoughts (obsessions) might be:

- A horrible thought that I may have said something inappropriate.

- A thought that there might be blood in my food.

- A thought that I am contaminated from the toilet.

People with OCD often ask if treatment can help them get rid of these intrusive thoughts, as they are so distressing and horrible. But if you instead consider whether all intrusive thoughts are always horrible you will see that they are not.

Usually people can think of an occasion when they suddenly had a thought that was helpful, such as suddenly remembering a friend’s birthday is coming up, or having a memory of a lovely holiday pop into their head. We can conclude from this that getting rid of intrusive thoughts themselves isn’t a realistic, or sometimes, desirable goal. It is also worth remembering that everyone has all sorts of intrusive thoughts – including the nasty ones: thoughts of harm coming to people, images of violence, urges to check things, doubts about whether they have done something. The difference with other people is that their intrusive thoughts do not become bothersome and stick.

Challenging the meaning attached to the thoughts

In CBT the person with OCD will explore alternative meanings or beliefs about the intrusive thoughts and rituals in all their guises (for example washing, checking, writing lists, tapping, touching, repeating, cleaning, trying to get a ‘just right’ feeling, praying) and will learn what it is that ultimately keeps the meaning they attach to such thoughts and rituals going.

So during the first few sessions a good therapist should spend time making sense of how a person’s OCD works and what keeps it going. The idea and reason behind this is that if we can understand the factors that keep a problem alive, we can then take the next step, which is to think about alternative ways of viewing the problem and what we can then do to change it.

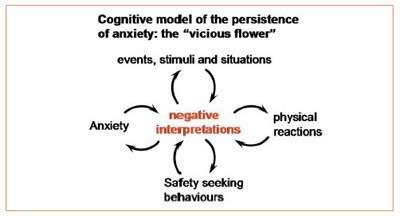

Therefore CBT looks at how OCD convinces you that the rituals and compulsions performed are necessary, in order to prevent something bad happening. If such a bad outcome were to be true as a result of the thought, the sufferer would be convinced it was entirely their fault and responsibility. We also look at the possibility that OCD is a liar. All the sufferer’s coping strategies have come about in the first place to make them feel safer and less anxious, when in fact they do the exact opposite, they make the person feel unsafe and scared. Even if they provide temporary relief from anxiety, the rituals make the meaning attached to the intrusive thoughts, images, urges and doubts feel even stronger, therefore becoming necessary for the sufferer to keep doing the rituals continuously. Ultimately making the thoughts seem even more real, and like there is even more truth in them.

The cyclical nature of the problem can be illustrated by drawing a diagram of how it works – the ‘vicious flower’.

So how does CBT work in practical situations?

OCD makes people feel they have to avoid all sorts of objects, people and places (for example public toilets, children’s playgrounds, people with diseases etc), but by avoiding such situations the sufferer never has the chance to find out what would really happen. So in CBT, people are asked to consider doing the opposite to avoiding the situation. So for example if OCD has made a person believe that they are at risk of dying from contamination from germs on a toilet – in treatment the therapist and patient might put their hands down the toilet. This behavioural experiment allows the person to find evidence for themselves about whether OCD has been lying and whether they have been needlessly avoiding situations for no reason at all. Of course, this is not straight forward, and the therapist will work with the patient to help them understand their worries and fears, to be able to approach such a challenging behavioural exercise.

Trying to not have certain thoughts is another common example of avoidance. However, the more we try and avoid and ignore unwanted intrusive thoughts, the stronger the frequency becomes. In fact we can experiment with this idea in treatment. Have you heard of the ‘pink fluffy bunny rabbit’ example (or sometimes pink elephant)? When asked to not think of pink fluffy bunny rabbits or their fluffy pink faces, you usually can’t think of anything else but pink fluffy bunny rabbits with fluffy pink faces! Try it out, look at the image for one minute, then tell yourself not to think of the pink fluffy bunny rabbit… still thinking of the pink fluffy bunny rabbit?

Trying to not have certain thoughts is another common example of avoidance. However, the more we try and avoid and ignore unwanted intrusive thoughts, the stronger the frequency becomes. In fact we can experiment with this idea in treatment. Have you heard of the ‘pink fluffy bunny rabbit’ example (or sometimes pink elephant)? When asked to not think of pink fluffy bunny rabbits or their fluffy pink faces, you usually can’t think of anything else but pink fluffy bunny rabbits with fluffy pink faces! Try it out, look at the image for one minute, then tell yourself not to think of the pink fluffy bunny rabbit… still thinking of the pink fluffy bunny rabbit?

So if you have persistent and distressing thoughts, despite it making sense to want to banish them from your mind, in actual fact it is a counterproductive strategy. In CBT, we might actually bring on the thoughts to show that having thoughts doesn’t actually matter or mean anything, with the ultimate aim of proving OCD to be a liar.

If a person believes that they are responsible for harm, or capable of being a paedophile, or that they can’t be trusted to lock their house, it seems like a good idea to seek reassurance and ask someone close to you to tell you otherwise. Unfortunately this reassurance seeking is a compulsion and ends up strengthening the belief that you really are responsible for or capable of such things, thus keeping the anxiety high and driving the OCD cycle. CBT will encourage the sufferer not to ask for reassurance, and see what happens to their obsessional belief.

OCD makes a person more likely to spot ‘risky’ situations and to notice intrusive thoughts. This makes it seem as if the world really is a dangerous place, and increases anxiety. CBT helps a person consider the possibility that there is a risk attached to most things, and experiments with whether being on ‘full alert’ the whole time makes their OCD belief weaker or stronger.

Take this example from popular culture. On ‘Who wants to be a Millionaire’, when Chris Tarrant (or Jeremy Clarkson now) says ‘Are you sure? Is that your final answer?’ – does that make the contestant feel more or less anxious? Usually, a contestant’s belief in whether they know the right answer suddenly disappears or significantly lowers when they’re under pressure and start asking themselves, “is that definitely correct?” The more they question themselves, the less certain they are.

It’s exactly the same with OCD, the more you check or carry out other compulsions to be ‘safe’ and ‘certain’, the less certain you usually become.

OCD often makes people mentally check or argue with themselves, and the person with OCD will be asked to try not to engage in these arguments, and see what happens. These types of behavioural approaches deliberately create anxiety, but at a level the person with OCD is ready to tolerate, often in a very structured and hierarchical step-by-step approach, starting with small exposure exercises, building up to much more difficult ones.

So one of the first steps the person with OCD may be asked to do in therapy – and in fact one which they could start before therapy begins – is to describe the obsessions and compulsions and rank them with the most severe ones at the top, and the least severe at the bottom. This is called the graded hierarchical approach where you start challenging your OCD from the easiest to the hardest.

How can CBT help with ‘Pure O’?

A common question we often receive is “how does CBT work for ‘Pure O’ intrusive thoughts? there are no exercises to do!”, but as mentioned in a previous section, ‘Pure O’ is just standard OCD and is no different to any other form of OCD with both obsessions and compulsions to work on. It’s about challenging our thoughts, and a therapeutic example might be to purposely bring on the unwanted OCD thoughts for their behavioural exercises. CBT will also help a patient recognise their compulsive behaviours, such as seeking reassurance, avoidance and checking for physical body reactions.

Summary

Remember, OCD is ‘Just a Thought’ and what CBT will teach people is that it’s not the thoughts themselves that are the problem; it’s what people make of those thoughts in the first place.

A key stage in the evolution of CBT was the development of ‘Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP)’ which involves being exposed to whatever it is that makes a person feel anxious, without checking or carrying out other rituals. You can read more about ERP on the next page.

What to read next: